Selasa, 18 Mei 2010

Senin, 17 Mei 2010

Gullian Barre Syndrome

GBS (Guillain Barre syndrome) is an autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks part of the peripheral nervous system myelin (demielinasi) and axons (axonal degeneration). Axons are long, single protrusion that delivers information from the cell body. Myelin is the sheath that surrounds axons, is a protein-lipid complex is white. GBS characterized by an overall polyneuropathy: paralysis of limbs, upper body and face; disappearance of tendon reflexes, decreased sensory functions (pain and temperature) from the body to the brain; autonomous dysfunctions and respiratory depression. Symptoms usually slowly, starting from the bottom up.

All forms of Guillain–Barré syndrome are due to an immune response to foreign antigens (such as infectious agents) that are mistargeted at host nerve tissues instead. The targets of such immune attack are thought to be gangliosides, compounds naturally present in large quantities in human nerve tissues. The most common antecedent infection is the bacteria Campylobacter jejuni. However, 60% of cases do not have a known cause; one study suggests that some cases are triggered by the influenza virus, or by an immune reaction to the influenza virus

Many terms have been used for the disease include, infectious polyneuritis, acute demyelinating segmentally Polyradiculoneuropathy, acute facial diplegia with polyneuritis, acute polyradiculitis, or Guillain Barre Strohl Syndrome.

The end result of such autoimmune attack on the peripheral nerves is damage to the myelin, the fatty insulating layer of the nerve, and a nerve conduction block, leading to a muscle paralysis that may be accompanied by sensory or autonomic disturbances.

The exact cause of GBS is unknown. Incidence of GBS is often preceded by the following things: (1) respiratory tract infection or ganstrointestinal tract (in two thirds of cases), (2) vaccination. The mechanism underlying the emergence of GBS is an abnormal response of T cells due infection

Cellular and humoral immune mechanisms appear a role, early inflammatory lesions will cause infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages in myelin components. At the electron microscope image shows that macrophages destroy the myelin sheath. Humoral immune factors such as antibodies, antimielin, and the complement is involved in the process oponisasi macrophages in Schwann cells. This process can be observed either on the nerve roots, peripheral nerves, and cranial nerves. Cytokines were also played, as shown by the correlation of clinical tumor necrotic factor (TNF) with weight disorders elektrofisiologik.

Since the reduction in disease poliomyelitis in the world, GBS becomes the most common acute paralytic disease, especially in Western countries with prevalence of 1.3 to 1.8 cases per 100,000 people. In the United States, the incidence of GBS ranges from 0.4 to 2.0 people per 100,000, but from the research at several hospitals in frequency estimates as many as 15%. Did not reveal any relationship with the incidence of GBS season in the United States second.

GBS immune response is believed to directly attack the components of aksolema glikolipid and myelin sheath. Antibody on peripheral nerve activates the complement system and macrophages, which would appear to depend on cellular cytotoxicity antibody against myelin components and aksolemma.

Damage to the myelin sheath will cause demielinasi segmental, which causes decreased nerve conductivity, and conduction velocity block. Axonal type of GBS is also known as SAFE, mainly characterized by axonal damage that nyata.5

In the first era of modern medicine, there is GBS disease similar to that found by Landry at the year 1859. Later, Osler in 1892 to develop in more detail the number of disease called acute febrile polyneuritis. In 1916, Guillan, Barre, and Strohl described more clinical symptoms and was first put forward about the picture on the state of cerebrospinal fluid, cytology dissociation of albumin (in normal cerebrospinal fluid protein elevation there).

Currently, the epidemic disease which resembles GBS is found every year in some areas of North China, mainly occurs in summer. This epidemic of Campylobacter jejuni associated with infection, and many antiglikolipid antibodies found in patients. Because this disease causes degeneration of peripheral motor axons without much inflammation, this syndrome is called Acute Motor Axonal Neuropathy (AMAN). SECURE contained in <10% of patients with GBS in Western countries and> 40% in China and Japan.

However, in mild cases, nerve axon (the long slender conducting portion of a nerve) function remains intact and recovery can be rapid if remyelination occurs. In severe cases, axonal damage occurs, and recovery depends on the regeneration of this important tissue. Recent studies on the disorder have demonstrated that approximately 80% of the patients have myelin loss, whereas, in the remaining 20%, the pathologic hallmark of the disorder is indeed axon loss

Currently research is being concentrated on anti-gangliosid antibodies contained in the strains of Campylobacter jejuni. These antibodies attack normal gangliosid located on peripheral nerve tissue.

Minggu, 16 Mei 2010

Eating Disorders

Definition and causes

Eating disorders are syndromes characterized by severe disturbances in eating behavior and by distress or excessive concern about body shape or weight. Presentation varies, but eating disorders often occur with severe medical or psychiatric comorbidity. Denial of symptoms and reluctance to seek treatment make treatment especially challenging.

Classification

Major eating disorders can be classified as anorexia nervosa , bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified. Although criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM IV-TR1), allow diagnosis of a specific eating disorder, many patients demonstrate a mixture of both anorexia and bulimia. Up to 50% of patients with anorexia nervosa develop bulimic symptoms, and a smaller percentage of patients who are initially bulimic develop anorexic symptoms.

| Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa |

|---|

|

| Type |

|

| Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa |

|---|

|

| Type |

|

| Criteria for Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified |

|---|

Eating disorder not otherwise specified includes disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for any specific eating disorder.

|

| Binge-eating disorder is recurrent episodes of binge eating in the absence if regular inappropriate compensatory behavior characteristic of bulimia nervosa. |

Listed in the DSM IV-TR appendix, binge eating disorder is defined as uncontrolled binge eating without emesis or laxative abuse. It is often, but not always, associated with obesity symptoms. Night eating syndrome includes morning anorexia, increased appetite in the evening, and insomnia. Often obese, these patients can have complete or partial amnesia for eating during the night.

Eating disorders before puberty include food avoidance emotional disorder, which is similar to anorexia; selective eating of only a few foods; pervasive refusal syndrome, with reduced intake and added behavioral problems; and functional dysphagia with no organic etiology. Unpleasant mealtimes and conflicts over eating can precede these conditions of childhood. Pica and rumination are not considered eating disorders, but rather are feeding disorders of infancy and childhood.

Gender Prevalence

Both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are more commonly seen in girls and women. Estimates of female-to-male ratio range from 6 : 1 to 10 : 1.

Lifetime Prevalence

The reported lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa among women has ranged from 0.5% when narrowly defined to 3.7% for more broadly defined anorexia nervosa. With regard to bulimia nervosa, estimates of lifetime prevalence among women range from 1.1% to 4.2%. Prevalence of eating disorders in young children is unknown. However, children as young as 5 years have reported awareness of dieting and know that inducing vomiting can produce weight loss. Eating disorder not otherwise specified is the most prevalent eating disorder.

Cultural Considerations

Eating disorders are more common in industrialized societies where there is an abundance of food and being thin, especially for women, is considered attractive. Eating disorders are most common in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. However, rates are increasing in Asia, especially in Japan and China, where women are exposed to cultural change and modernization. In the United States, eating disorders are common in young Latin American, Native American, and African American women, but the rates are still lower than in white women. African American women are more likely to develop bulimia and more likely to purge. Female athletes involved in running, gymnastics, or ballet and male body builders or wrestlers are at increased risk.

Pathophysiology and natural history

Biologic and psychosocial factors are implicated in the pathophysiology, but the causes and mechanisms underlying eating disorders remain uncertain.

Biologic Factors

First-degree female relatives and monozygotic twin offspring of patients with anorexia nervosa have higher rates of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Children of patients with anorexia nervosa have a lifetime risk for anorexia nervosa that is tenfold that of the general population (5%). Families of patients with bulimia nervosa have higher rates of substance abuse, particularly alcoholism, affective disorders, and obesity.

Endogenous opioids might contribute to denial of hunger in patients with anorexia nervosa. Some hypothesize that dieting can increase the risk for developing an eating disorder. Increased endorphin levels have been described in patients with bulimia nervosa after purging and may be likely to induce feelings of well being. Diminished norepinephrine turnover and activity are suggested by reduced levels of 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol in the urine and cerebrospinal fluid of some patients with anorexia nervosa. Antidepressants often benefit patients with bulimia nervosa and support a pathophysiologic role for serotonin and norepinephrine.

Starvation results in many biochemical changes such as hypercortisolemia, nonsuppression of dexamethasone, suppression of thyroid function, and amenorrhea. Several computed tomography (CT) studies of the brain have revealed enlarged sulci and ventricles, a finding that is reversed with weight gain. In one study using positron emission tomography (PET), metabolism was higher in the caudate nucleus during the anorectic state than after hyperalimentation.

Anorexia risk may increase with a polymorphism of the promoter region of serotonin 2a receptor. The melanocortin 4 receptor gene is hypothesized to regulate weight and appetite. Polymorphism in the gene for agouti-related peptide might also play a role at the melancortin receptor. In bulimia nervosa there is excessive secretion of ghrelin. Ghrelin receptor gene polymorphism is associated with both hyperphagia of bulimia and Prader-Willi syndrome.

Perhaps some of the most fascinating new research addresses the overlap between uncontrolled compulsive eating and compulsive drug seeking in drug addiction. Reduction in ventral striatal dopamine is found in both of these groups. The lower the frequency of dopamine D2 receptors, the higher the body mass index. Obese persons might eat to temporarily increase activity in these reward circuits. Frequent visual food stimuli paired with increased sensitivity of right orbitofrontal brain activity is likely to initiate eating behavior. Marijuana's well-known appetite stimulant effect is likely due to its agonist activity at cannabinoid receptors, and cannabinoid receptor antagonism has been associated with reduced binge eating.

Psychosocial Factors

High levels of hostility, chaos, and isolation and low levels of nurturance and empathy are reported in families of children presenting with eating disorders. Anorexia has been postulated as a reaction to demands on adolescents to behave more independently or to respond to societal pressures to be slender. Anorexia nervosa patients are usually high achievers, and two thirds live at home with parents. Many consider their bodies to be under the control of their parents. Family dynamics alone, however, do not cause anorexia nervosa. Self tarvation may be an effort to gain validation as a unique person. Patients with bulimia nervosa have been described as having difficulties with impulse regulation.

Course and Prognosis

As a general guideline, it appears that one third of patients fully recover, one third retain subthreshold symptoms, and one third maintain a chronic eating disorder.

Anorexia Nervosa

Long-term follow-up shows recovery rates ranging from 44% to 76%, with prolonged recovery time (57 to 59 months). Mortality (up to 20%) is primarily from cardiac arrest or suicide. Good prognostic factors are admission of hunger, lessening of denial, and improved self esteem. Poorer prognostic factors are initial lower minimum weight, presence of vomiting or laxative abuse, failure to respond to previous treatment, disturbed family relationships, and conflicts with parents.

Bulimia Nervosa

Little long-term follow-up data exist. Short-term success is 50% to 70%, with relapse rates between 30% and 50% after 6 months. These patients have an overall better prognosis as compared with anorexia nervosa patients. Poor prognostic factors are hospitalization, higher frequency of vomiting, poor social and occupational functioning, poor motivation for recovery, severity of purging, presence of medical complications, high levels of impulsivity, longer duration of illness, delayed treatment, and premorbid history of obesity and substance abuse.

Signs and symptoms

Anorexia Nervosa

The essential features of anorexia nervosa are refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight, intense fear of gaining weight, and significant disturbance in the perception of the shape or size of one's body. Patients commonly lack insight into the problem and are brought to professional attention by a family member. DSM IV-TR identifies two subtypes of anorexia nervosa: restricting type and binge eating–purging type. Comorbid psychiatric symptoms include depressive symptoms such as depressed mood, social withdrawal, irritability, insomnia, and decreased sexual interest. Many depressive features may be secondary to the physiologic sequelae of semistarvation. Symptoms of mood disturbances need to be reassessed after partial or complete weight restoration. Obsessive-compulsive features—thoughts of food, hoarding food, picking or pulling apart small portions of food, or collecting recipes—are common. Anxiety symptoms and concerns of eating in public are also common.

Bulimia Nervosa

The essential features are binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behavior such as fasting, vomiting, using laxatives, or exercising to prevent weight gain. Binge eating is typically triggered by dysphoric mood states, interpersonal stressors, intense hunger following dietary restraints, or negative feelings related to body weight, shape, and food. Patients are typically ashamed of their eating problems, and binge eating usually occurs in secrecy. Unlike anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa patients are typically within normal weight range and restrict their total caloric consumption between binges.

Diagnosis

Rating Instruments

In addition to the clinical interview, the Eating Attitudes Test, Eating Disorders Inventory, Body Shape Questionnaire, and others can be used to assess eating disorders.

Comorbidity of Eating Disorders

Psychiatric

Common comorbid conditions include major depressive disorder or dysthymia (50% to 75%), sexual abuse (20% to 50%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (25% with anorexia nervosa), substance abuse (12% to 18% with anorexia nervosa, especially the binge–purge subtype, and 30% to 37% with bulimia nervosa), and bipolar disorder (4% to 13%).

Medical

There are many complications related to weight loss, purging and vomiting, and laxative abuse. When obesity is associated with the eating disorder, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, joint injury, hypertension, and cardiac and respiratory disorders can result.

| Medical Complications of Eating Disorders |

|---|

| Weight Loss |

|

| Appetite Suppressant Abuse |

|

| Purging (Abuse of Laxatives, Ipecac, or Diuretics) |

|

Differential diagnosis

Anorexia Nervosa

Medical illnesses include brain tumors and other malignancies, gastrointestinal disease, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Other psychiatric disorders with disturbed appetite or food intake include depression, somatization disorder, and schizophrenia. Patients with depressive disorder generally do not have an intense fear of obesity or body image disturbance. Depressed patients usually have a decreased appetite, whereas anorexia nervosa patients claim to have a normal appetite and to feel hungry. Patients with somatization disorder do not generally express a morbid fear of obesity. Severe weight loss and amenorrhea of more than 3 months are unusual in somatization disorder. Schizophrenic patients might have delusions about food being poisoned but rarely are they concerned with caloric content. They also do not express a fear of gaining weight.

Bulimia nervosa patients usually maintain their weight within a normal range.

Bulimia Nervosa

General medical conditions of central nervous system pathology, such as brain tumors, can simulate bulimia nervosa. Kluver-Bucy syndrome is a rare condition characterized by hyperphagia, hypersexuality, and compulsive licking and biting. Klein-Levin syndrome, also rare, is more common in men and consists of hyperphagia and periodic hypersomnia.

Patients with the binge–purge subtype of anorexia nervosa fail to maintain their weight within a normal range. Patients with borderline personality disorder sometimes binge eat but do not have other criteria for bulimia nervosa.

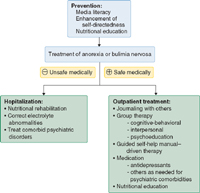

Treatment

A comprehensive treatment plan including a combination of nutritional rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and medication is recommended. The patient's weight and cardiac and metabolic status determines the acuteness of the illness and the need for hospitalization. Treatment guidelines are well documented by the American Psychiatric Association in its practice guideline for treating eating disorders.

| Indications for Hospitalization |

|---|

| Weight <75% of individually estimated healthy weight |

| Rapid, persistent decline in oral intake or weight despite maximally intensive outpatient interventions |

| Prior knowledge of weight at which physical instability is likely to occur in the particular patient |

Serious physical abnormalities

|

| Comorbid psychiatric illness (suicidal, depressed, unable to care for self, etc.) |

Aims of treatment are to restore the patient's nutritional status and establish healthy eating patterns, treat medical complications, correct core dysfunctional thoughts related to the eating disorder, enlist family support, and provide family counseling.

Nutritional Rehabilitation

Expected rates of controlled weight gain should be 2 to 3 pounds per week for inpatients and 0.5 to 1 pound per week for outpatients. Intake levels should start at 30 to 40 kcal/kg per day (1000-1600 kcal/day) in divided meals. If oral feeding is not possible, progressive nocturnal nasogastric feeding can lessen distress (physical and psychological) during early weight gain.

Daily morning weights, vital signs, fluid intake, and urine output should be measured. Frequent physical examinations should be performed to detect circulatory overload, refeeding edema, and bloating. Monitor serum electrolyte levels (low potassium or phosphorus), and get an electrocardiogram if needed.

Stool softeners, not laxatives, should be used to treat constipation. The diet should be supplemented with vitamins and minerals.

Patients should be given positive reinforcement (praise) and negative reinforcement (restrictions of exercise and purging). They should be closely supervised, and access to bathrooms should be restricted for at least 2 hours after meals. After weight restoration has progressed, stretching can begin, followed by gradual re-introduction of aerobic exercise.

Psychosocial Treatment

Psychosocial treatments are required during hospitalization as well as after discharge. Commonly used models include dynamic expressive-supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral techniques (planned meals and self-monitoring, exposure, and response prevention). Research data more strongly support the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapies. Although cognitive-behavioral therapy is important, its benefits increase with the addition of a nutritional component.

Group therapy, support groups, and 12-step programs like Overeaters Anonymous may be useful as adjunctive treatment and for relapse prevention. Family therapy and marital therapy are helpful in cases of dysfunctional family patterns and interpersonal distress.

Guided self-help manuals can reduce the number of binge–purge episodes in at least some patients with bulimia nervosa. In fact, a manual-driven self-help approach incorporating cognitive-behavioral principles combined with keeping contact with a general practice physician in one study did as well as specialist-based treatment in reducing bulimic episodes. Computer-based health education can improve knowledge and attitudes as a patient-friendly adjunct to therapy.

One unique approach is a behavioral family-based therapy for elementary school–age children with behavioral problems, disordered eating, and obesity. Children and parents were examined and tested before and after the intervention and all lost weight. Although eating disorders did not resolve, other behavioral problems did. There was less parental dissatisfaction as children developed better awareness and behavior patterns.

Higher self-directedness at baseline is a good predictor of improvement at the end of a variety of interventions, as well as follow-up 6 to 12 months later. This might help explain why manual-driven self-help and psychoeducational programs that emphasize improvement of self-esteem and reassessment of body image have achieved some success.

Medication

Anorexia Nervosa

The evidence for significant efficacy is lacking, with very few methodologically sound studies. Although medication is less successful in anorexia nervosa than in bulimia nervosa, it is most often used in anorexia nervosa after weight has been restored but may begin earlier when indicated. Medication helps maintain weight and normal eating behavior and can treat associated psychiatric symptoms.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., fluoxetine) are commonly considered for patients with anorexia nervosa who have depressive, obsessive, or compulsive symptoms that persist in spite of or in the absence of weight gain. Tricyclic antidepressants are also effective in treating eating disorders. However, they should be used with caution, because they have greater risks of cardiac complications, including arrhythmias and hypotension.

Low doses of antipsychotics may be used for marked agitation and psychotic thinking, but they can frighten patients by increasing appetite dramatically, particularly if the patient is not psychotic. Antianxiety medications, such as benzodiazepines, may be used for extreme anticipatory anxiety concerning eating.

Estrogen replacement alone does not generally appear to reverse osteoporosis or osteopenia, and unless there is weight gain, it does not prevent further bone loss. There is very limited evidence of bisphosphonate's efficacy in treating associated osteoporosis.

Promotility agents such as metoclopramide are commonly used for bloating and abdominal pains due to gastroparesis and premature satiety, but they require monitoring for drug-related extrapyramidal side effects.

Recombinant human growth hormone has helped stabilize patients medically in shorter hospital stays.

Bulimia Nervosa

Antidepressants are used primarily to reduce the frequency of disturbed eating and treat comorbid depression, anxiety, obsessions, and certain impulse-disorder symptoms. Medication can reduce binge episodes, but is not sufficient to be the sole treatment. The only medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for bulimia nervosa is the SSRI fluoxetine (Prozac). Several studies have demonstrated efficacy of other SSRIs including sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), and citalopram (Celexa); tricyclic antidepressants including imipramine (Tofranil), nortryptyline (Pamelor), and desipramine (Norpramin); and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) including tranylcypromine (Parnate). Doses of tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs parallel those used to treat depression, but higher doses of fluoxetine (up to 80 mg/day) may be needed to treat bulimia nervosa. Bupropion (Wellbutrin) has been associated with seizures in purging bulimic patients and its use is not recommended.

Other psychotropic drugs are sometimes used. Lithium continues to be used occasionally as an adjunct for comorbid disorders. Various anticonvulsants have successfully reduced binge eating for some patients, but they can also increase appetite. Topiramate lowers appetite but has been associated with cognitive side effects. Sibutramine has also been used to reduce appetite in bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.

Screening and prevention

Prevention programs presented in schools to both genders or through organizations like the Girl Scouts have been successful in reducing risk factors for eating disorders. Often focusing on media literacy and interactive discussion, there are increasing reports of short-term and longer-term benefits in body satisfaction and acceptance of normal growth.

Sputum Cultures

Sputum is not material from the postnasal region and is not spittle or saliva. A sputum specimen comes from deep within the bronchi. Effective coughing usually enables the patient to produce a satisfactory sputum specimen.

Indication for Collection

Sputum cultures are important for diagnosis of the following condition:

1. Bacterial pneumonia

2. Pulmonary TB

3. Chronic bronchitis

4. Bronchiectasis

5. Suspected pulmonary mycotic infections

6. Mycoplasmal pneumonia

7. Suspected viral pneumonia

Reference Values

Normal: negative normal oral flora

Produce

1. instruct patients to provide a deep cough specimen into sterile container. often, an early morning specimen is best. Expectorated material of 1 to 3 mL is sufficient for most examinations. remember that good sputum samples depend on through health care worker education and patient understanding during the collection process.

2. Label specimens properly and note to the suspected disease on the accompanying requistion.

3. Do not refrigerate speciments, and deliver to the laboratory as soon as possible.

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

1. Record sign and symptoms (eg. coughing, productive sputum, blood in sputum)

2. Instruct the patient that this test requires tracheobronchial sputum deep in the lungs. Instruct the patient to take two or three deep breaths, then to take another deep breath and forcefully cough with exhalation.

3. Ask respiratory therapy personnel to assist the patient in obtaining an "aerosol-induced" specimen if the cough is not productive. Patients breathe aerosolized droplets of a sodium chloride-glycerine solution until a strong cough reflex is initiated. It should be noted on the requesition as being aerosol induced.

4. Remember that when pleural empyema is present, thoracentesis fluid and blood culture are excellent diagnostic speciment. Bronchial washing,BAL, and bronchial brush cultures are excellent for detecting most major pathogens of the respiratory ract.

Posttest Patient Care

1.Interpret test outcomes, counsel about treatment, and monitor for respiratory tract infections.

Indication for Collection

Sputum cultures are important for diagnosis of the following condition:

1. Bacterial pneumonia

2. Pulmonary TB

3. Chronic bronchitis

4. Bronchiectasis

5. Suspected pulmonary mycotic infections

6. Mycoplasmal pneumonia

7. Suspected viral pneumonia

Reference Values

Normal: negative normal oral flora

Produce

1. instruct patients to provide a deep cough specimen into sterile container. often, an early morning specimen is best. Expectorated material of 1 to 3 mL is sufficient for most examinations. remember that good sputum samples depend on through health care worker education and patient understanding during the collection process.

2. Label specimens properly and note to the suspected disease on the accompanying requistion.

3. Do not refrigerate speciments, and deliver to the laboratory as soon as possible.

Interventions

Pretest Patient Care

1. Record sign and symptoms (eg. coughing, productive sputum, blood in sputum)

2. Instruct the patient that this test requires tracheobronchial sputum deep in the lungs. Instruct the patient to take two or three deep breaths, then to take another deep breath and forcefully cough with exhalation.

3. Ask respiratory therapy personnel to assist the patient in obtaining an "aerosol-induced" specimen if the cough is not productive. Patients breathe aerosolized droplets of a sodium chloride-glycerine solution until a strong cough reflex is initiated. It should be noted on the requesition as being aerosol induced.

4. Remember that when pleural empyema is present, thoracentesis fluid and blood culture are excellent diagnostic speciment. Bronchial washing,BAL, and bronchial brush cultures are excellent for detecting most major pathogens of the respiratory ract.

Posttest Patient Care

1.Interpret test outcomes, counsel about treatment, and monitor for respiratory tract infections.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in the United States. The incidence increases with advancing age. Many patients can achieve significant relief of their symptoms with appropriate care. Current therapies are being investigated to see if they improve the long-term outcomes of this disease. Ongoing research is aiming to identify patients who have a more rapidly progressive illness, and it is evaluating disease-specific molecular pathways as potential new targets for intervention. Advances in joint replacement surgery have made this an excellent treatment for many patients with more severe disease.

Definition

Osteoarthritis (also known as degenerative arthritis, hypertrophic arthritis, or age-related arthritis) implies an inflamed joint by its very name, but for a long time the role of inflammation in osteoarthritis has been somewhat controversial. The pathology reflects the result of joint disease, with loss and erosion of articular cartilage, subchondral sclerosis, and bone overgrowth (osteophytes).

Rather than one uniform disease, osteoarthritis may be either a primary or an idiopathic phenomenon or it may be secondary to some other disorder. Osteoarthritis is also commonly seen as a secondary form of arthritis in patients with other inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Mechanical and genetic factors play roles in the development of this disease as well. Histologic evidence clearly shows ongoing inflammation and cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis, although not to the same degree as in other arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Pathophysiology

Understanding the metabolic pathways at the molecular level has greatly enhanced our understanding of the tissue factors involved.

Although the role of inflammation in osteoarthritis has been unclear for a long time, significant progress has been made in more recent years. The molecular pathways involved are being more clearly defined, and this is an area of intense ongoing research. Studies also show that there are ongoing inflammation and synovitis that result in permanent joint damage. At times, this may be more striking, with flares of symptoms or joint effusions. Effusions can be very large at times, and we have aspirated more than 100 mL of fluid from an acutely swollen knee on more than one occasion. Biopsies of synovium from patients with osteoarthritis show more inflammatory infiltrates than normal controls do.

Some patients appear to have a more hereditary form of this disease. The striking features are usually seen in women who, shortly after menopause, develop distal (Heberden's nodes) and proximal (Bouchard's nodes) interphalangeal joint involvement in their hands, which eventually leads to the characteristic bony swelling, and correlates with the presence of radiographic knee involvement. Previous trauma or other prior joint insults like inflammation, infection, or avascular necrosis increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis at that anatomic site.

Histologically, articular cartilage comprises chondrocytes and their extracellular matrices. Three distinct zones are recognizable—superficial, middle, and deep. Mechanical or inflammatory injury that disrupts these zones can lead to irreparable damage and to further inflammation and cartilage degradation as the body attempts to heal itself. In essence, there is a defective repair mechanism, resulting in scarring, thinning, and erosion of the articular cartilage in the joints of subjects with osteoarthritis. Several cytokines, such as interleukin-1-β and transforming growth factor-β, proteases (the most important of which is matrix metalloprotease), and nitric oxide synthetase all appear to be essential for cartilage degradation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. It was previously believed that bone changes occur later in this disease, but newer evidence suggests that subchondral bone changes might take place earlier than previously suspected. Increased production of bone and cartilage degradation products has been shown to herald more rapid disease progression.

Symptoms, Signs, and Diagnosis

Stiffness, joint pain, and swelling are the earliest symptoms of osteoarthritis. In contrast to inflammatory arthritis, the pain of osteoarthritis is often exacerbated by activity or weight bearing and relieved by rest. Early symptoms are usually of an insidious nature and often do not correlate well with radiographic abnormalities. Later, extensive bone changes, muscle weakness, and loss of joint integrity can lead to more dramatic joint deformity and disability. Physical findings include painful limitation of movement, bony crepitus, and, occasionally, joint effusions and joint line or bone tenderness. As the disease progresses, more permanent joint deformities can occur in the forms of contractures, osteophytes, and loss of joint function.

Synovial fluid analyses and laboratory investigations are generally not diagnostic. Their usefulness lies mainly in excluding other causes for the patient's symptoms or other common forms of arthritis such as crystal deposition diseases. Newer studies using markers of bone, cartilage, and synovium turnover might help identify patients who have a more rapidly progressive form of joint disease, but they are not recommended in routine clinical practice. Data on high-sensitivity, C-reactive protein have been reported, with somewhat conflicting findings. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein appear to correlate best with symptoms of pain and stiffness rather than extent or progression of disease.

Radiographic studies are reserved for patients with symptoms. Again, they are useful in excluding other causes of the patient's symptoms and to evaluate the extent of joint pathology. However, although radiographs might show osteoid changes such as joint-space narrowing, effusions, bone cysts, and osteophytes, radiographs are limited in sensitivity and in their ability to show nonosseous structures.

Ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show more extensive joint detail. Although changes in soft tissue and cartilage are better visualized by MRI than by radiographs, and MRI is more sensitive for picking up early bone changes, this is generally unhelpful to the practicing physician. Felson and colleagues have shown that men with osteoarthritis of the knee who have MRI evidence of subchondral bone bruising or marrow edema experience a more rapid progression of their disease than men who have none. Joint malalignment correlates strongly with the presence of the bone marrow lesions. In addition, asymptomatic patients with osteoarthritis might have significant abnormalities on MR imaging, making abnormal findings even harder to interpret. These more-expensive imaging modalities are usually reserved for evaluating other possible causes of symptoms, such as meniscal tears and tumors. Until it can be shown that a therapeutic intervention can significantly prevent or retard the progression of this disease, the role of these imaging modalities in osteoarthritis is of limited value.

Treatment

Treatments have not been shown to reverse this disease, although some treatments can halt its progression. The goal of treatment is adequate pain relief and preservation of function. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have published guidelines for managing hip and knee osteoarthritis.

Weight loss, even small amounts, can significantly benefit overweight arthritis patients. Relaxation programs and moderate exercise, good nutrition, and education can all help relieve suffering in arthritis patients. Caring health care professionals can alleviate worry and help a patient to achieve realistic goals. Devices such as canes, supports, and braces can take some stress off the affected joint. Avoiding aggravating factors such as trauma, excessive weight gain, or overly strenuous exercise is essential. Other analgesic therapies, such as heating pads or ice packs, also alleviate suffering. Care should be taken, as in all pain-related illnesses, to treat concomitant aggravating factors such as psychosocial stress or other painful maladies, such as secondary bursitis.

Analgesics and Anti-Inflammatories

Acetaminophen (paracetamol in Europe) is generally recommended as first-line pharmacologic therapy. Acetaminophen is a relatively safe treatment with significantly lower gastrointestinal (GI), renal, and cardiovascular toxicities than other medications. When taken on a regular basis, doses of 500 to 750 mg three to four times daily can provide substantial relief. Care should be taken not to exceed 4 g/day. 2,3

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can provide significant acute relief in patients with osteoarthritis. However, because osteoarthritis occurs more commonly in older patients who often have other comorbidities, the use of NSAIDs is limited by their potential for or actual side effects. Notably, they can cause or worsen GI hemorrhage, renal insufficiency, congestive heart failure, and hypertension.

Several agents (e.g., rofecoxib, celecoxib) that specifically inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the United States and in Europe for use in arthritis patients. Although they are more expensive than over-the-counter generic drugs, they have a better GI safety profile. The concern with these newer agents, as for the older NSAIDs, is that there may be an increased risk of cardiovascular events for patients taking these medications. Indeed, one of these agents (rofecoxib [Vioxx]) was withdrawn from the market because of evidence documenting such side effects. Whether these findings are specific to rofecoxib or represent a class effect remains to be determined. They should be used with extreme caution or not at all in patients with renal or cardiovascular disease.

Topical aspirin or NSAID preparations, which are more widely available in Europe, are an alternative to oral medications. However, the incidence of side effects from NSAIDs is often dose related, and thus they should probably be reserved for acute flares or more recalcitrant disease.

Alternative Treatments

Viscosupplements, although approved by the FDA, appear to provide little more relief than sham injections. Despite the promise for these drugs, well-performed placebo-controlled trials have had disappointing results. Thus, we do not recommend routine use of intra-articular hyaluronate or its derivatives until there is stronger evidence that they are clearly beneficial.

Many patients with osteoarthritis use alternative therapies in an attempt to relieve their suffering. Natraceuticals have shown some promise in this regard. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are by far the most studied agents in this category and have been shown in several studies to be as effective as acetaminophen and NSAIDs, with significantly fewer adverse effects. These agents appear to significantly alleviate pain and suffering by an unknown mechanism. They have a slow onset of action (placebo-controlled trials show that it takes several weeks to see an effect in the treated groups), and they appear to have a more sustained post-treatment effect than NSAIDs or analgesics. A 3-year placebo-controlled trial showed that glucosamine might retard radiographic progression. We recommend trying glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate at a dose of 1200 to 1500 mg daily in most patients with osteoarthritis, given that the safety profile and efficacy are similar to those of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

Acupuncture, although used by many patients, appears to be no better than sham needling in controlled trials, and it is not without its own risks, which include reports of hepatitis transmission and pneumothoraces.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is probably one of the greatest killers of all times, over the centuries taking more than one billion lives and up to 2 million people every year (i.e., one life every 15 seconds, as opposed to a life lost in an accident every 50 seconds). Every year, TB infects up to 100 million people worldwide, and up to 8 million develop active disease. If not treated, every source case infects, on average, 10 to 15 other individuals each year. TB can be considered a social disease, disrupting families emotionally, educationally, and economically. Furthermore, only about 20% of worldwide TB cases are detected and treated successfully.

DOT strategy implemented by the World Heath Organization (WHO) is probably one of the most cost-effective of all health interventions. Achievement of global targets of 70% detection and 85% cure rates would reduce incidence and mortality by 10%. The United States and several other low-incidence countries have embarked on plans to eliminate tuberculosis completely. Important elements in an elimination strategy would be to identify and treat effectively LTBI persons at risk of developing active disease, and to ensure provision of inexpensive and efficacious drugs to countries that cannot afford them. However, even though a constellation of drugs, molecular tools, and public health strategies are on the horizon, newer diagnostic tools, a better vaccine, and novel therapeutic agents are urgently needed to fight this condition more effectively.

Causes

Tuberculosis is caused by a group of five closely related species, which form the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex—M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, M. microti, and M. canettii. M. tuberculosis (Koch's bacillus) is responsible for the vast majority of TB cases in the United States. The main defining characteristic of the genus Mycobacterium is the property called “acid-fastness,” which is the ability to withstand decolorization with an acid-alcohol mixture after staining with carbolfuchsin or auramine-rhodamine. Mycobacteria are primarily intracellular pathogens, have slow growth rates, are obligate aerobes, and produce a granulomatous reaction in normal hosts. In cultures, M. tuberculosis does not produce significant amounts of pigment, has a buff-colored, smooth surface appearance, and biochemically produces niacin. These characteristics are useful in differentiating M. tuberculosis from nontuberculous mycobacteria. One characteristic but not distinctive morphologic property of M. tuberculosis is the tendency to form cords, or dense clusters of bacilli, aligned in parallel (Fig 1). The biochemical background of cording is called cord factor (a trehalose dimycolate), and its contribution to bacterial virulence is still unclear.

Pathophysiology and natural history

TB transmission occurs almost exclusively from human to human; a prerequisite is having contact with a source case. More than 80% of new TB cases result from exposure to sputum smear–positive cases, although smear-negative, culture-positive cases can be responsible for up to 17% of new cases. Tuberculosis is spread by airborne droplet nuclei, which are 1- to 5-mm particles containing 1 to 400 bacilli each. They are expelled in the air by, for example, coughing, sneezing, singing, laughing, or talking, and remain suspended in the air for many hours. They can be inhaled and subsequently entrapped in the distal airways and alveoli. There, bacilli are ingested by local macrophages, multiply within the cells and, within 2 weeks, are transported through the lymphatics to establish secondary sites (lymphohematogenous spread). The development of an immune response, heralded by a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction over the next 4 weeks, leads to granuloma formation, with a subsequent decrease in the number of bacilli. Some of them remain viable, or dormant, for many years. This stage is called latent TB infection (LTBI), which is generally an asymptomatic, radiologically undetected process in humans. Sometimes, a primary complex (Ghon complex) can be seen radiographically, mostly in the lower and middle lobes, and comprises the primary lesion, hilar lymphadenopathy, with or without a lymphangitic track. Later, the primary lesion tends to become calcified and can be identified on chest radiographs for decades. Most commonly, a positive tuberculin test result remains the only proof of LTBI, and therefore does not signify active disease.

Under certain conditions of immature or disregulated immunity, alveolar macrophages and the subsequent biologic cascade could fail in limiting the mycobacterial proliferation, leading to primary progressive tuberculosis; this is seen mostly in children younger than 5 years or in HIV-positive or profoundly immunosuppressed individuals. Factors known to influence this unfavorable course are patient's age, nutritional status, host immunity, and bacterial infective load.

Once infected with M. tuberculosis, 3% to 5% of immunocompetent individuals will develop active disease (i.e., secondary progressive tuberculosis) within 2 years and an additional 3% to 5% later on during their lifetime. Overall, there is a lifetime risk of re-activation of 10%, with one half occurring during the first 2 years after infection—hence, the necessity to treat all tuberculin skin test converters. The lifetime re-activation rate is approximately 20% for most persons with purified protein derivative (PPD) induration of more than 10 mm and either HIV infection or evidence of old, healed tuberculosis; it is between 10% and 20% for recent PPD skin test converters, adults younger than 35 years with an induration of more than 15 mm or on therapy with infliximab (a tumor necrosis a [TNF-a] receptor blocker), and children younger than 5 years and a skin induration of more than 10 mm.

Studies performed in New York City and San Francisco using DNA fingerprinting have indicated that recent transmission (exogenous reinfection), especially among HIV patients, could account for up to 40% of new TB cases. This is significantly different from older studies, which have shown that approximately 90% of new TB cases are the result of endogenous re-activation.

After inhalation, the pathogenic bacilli start to replicate slowly and continuously and lead to the development of a cellular immunity in about 4 to 6 weeks. T lymphocytes and local (pulmonary and lymphatic node) macrophages represent key players in limiting further spread of bacilli in the host. This can be seen at the pathologic level, where the bacilli are in the center of necrotizing (caseating) and non-necrotizing (noncaseating) granulomas, surrounded by lymphocytes and macrophages. The infected macrophages release interleukins 12 and 18 (IL-12 and IL-18) which stimulate CD4-positive T lymphocytes to secrete IFN-γ (interferon gamma), which in turn activate the macrophage phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis and the release of TNF-a. TNF-α has an important role in granuloma formation and the control of infection.

Genetic defects are illustrated by different polymorphisms of the NRAMP-1 gene (natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1); vitamin D receptors, and interleukin-1 have also been shown to be involved in TB pathogenesis. It can be difficult to differentiate between genetic predisposition and overwhelming bacteriologic load, as often seen in countries with a high prevalence of TB.

HIV coinfection is the greatest risk factor for progression to active disease in adults. The relation between HIV and TB has augmented the deadly potential of each disease. Other risk factors include diabetes mellitus, renal failure, coexistent malignancies, malnutrition, silicosis, immunosuppressive therapies (including steroids and anti-TNF drugs), and TNF-α receptor, IFN-γ receptor, or IL-12 β1 receptor defects.

Diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms

A high index of suspicion is needed in countries with a high prevalence of infection or in patients with immunosuppression, although bacteriologic confirmation is required whenever possible. Persistent cough for more than 2 to 4 weeks should raise the possibility of pulmonary TB. Other common associated symptoms are hemoptysis, dyspnea, malaise, weight loss, night sweats, and chest pain. The symptoms are less pronounced in children, and any exposure to an active TB patient or a positive tuberculin test should raise more concerns about this disease.

Laboratory Tests

One inexpensive and rapid diagnostic test is the sputum smear, done by Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) carbolfuchsin, Kinyoun carbolfuchsin, or fluorochrome staining methods. ZN stain identifies 50% to 80% of culture-positive TB cases and is a useful diagnostic and epidemiologic tool, because smear-positive TB patients are more infectious than smear-negative patients and have a higher fatality rate. Nevertheless, smear-negative cases may account for up to 20% of M. tuberculosis transmission. In countries with a high prevalence of TB, a positive smear signifies TB in 95% of ases. The lower limit of detection of ZN staining s 5 × 10 3 organisms/mL, whereas rhodamine-auramine fluorochrome staining tends to be more sensitive. In children, M. tuberculosis can be recovered from gastric aspirates, with yields varying from 30% to 50% in older children to 70% in infants for three consecutive specimens. The role of induced sputum or bronchoscopy in diagnosing TB is well established in patients unable to provide good-quality sputum specimens.

Culture media most often used for diagnosis include the following:

Solid culture medium—egg-based Löwenstein-Jensen, or agar-based Middlebrook 7H10 or 7H11 (growth can take up to 6 weeks)

Liquid culture medium (growth in 1 to 3 weeks)

The speciation can be done with biochemical tests or DNA probes. The direct specimen polymerase chain reaction assay is rapid (1 to 2 days), although it can lead to false-positive results and has been disappointing in its practicality.

Imaging Studies

Radiographic findings suggesting TB include upper lobe infiltrates, cavitary lesions, and hilar or paratracheal lymphadenopathy. In many patients with primary progressive disease and in HIV patients, radiographic findings can be subtle and include lower lobe opacities, a miliary pattern, or both. In a study done on HIV-infected pulmonary TB patients, 8% of cases had normal chest radiographs.

Diarrhea

Definition and causes

Normal bowel frequency ranges from three times a day to three times a week in the normal population. Increased stooling, with stool consistency less solid than normal, constitutes a satisfactory, if somewhat imprecise, definition of diarrhea. Acute diarrhea is defined as a greater number of stools of decreased form from the normal lasting for less than 14 days. If the illness persists for more than 14 days, it is called persistent. If the duration of symptoms is longer than 1 month, it is considered chronic diarrhea. Most cases of acute diarrhea are self limited, caused by infectious agents (e.g. viruses, bacteria, parasites), and do not require medication unless the patient is immunocompromised.

Pathophysiology

Approximately 8 to 9 L of fluid enter the intestines daily—1 to 2 L represents food and liquid intake, and the rest is from endogenous sources such as salivary, gastric, pancreatic, biliary, and intestinal secretions. Most of the fluid, about 6 to 7 L, is absorbed in the small intestine, and only about 1 to 2 L is presented to the colon. Most of this is absorbed as it passes through the colon, leaving a stool output of about 100 to 200 g/day. Although many organisms simply impair the normal absorptive processes in the small intestine and colon, others, organisms, such as vibrio cholera, secrete a toxin that causes the colonic mucosa to secrete, rather than absorb, fluid and electrolytes. Voluminous diarrhea may result.

Diarrhea-causing pathogens are usually transmitted through the fecal-oral route. Risk factors for this type of transmission include improper disposal of feces and lack of proper hand washing following defecation and feces contact before handling food. Other risk factors include improper food hygiene, inadequate food refrigeration, food exposure to flies, and consumption of contaminated water. Multiple host factors that determine the level of illness once exposure to infectious agents has occurred include age, personal hygiene, gastric acidity and other barriers, intestinal motility, enteric microflora, immunity, and intestinal receptors.

Viruses (e.g., adenovirus, rotavirus, Norwalk virus) are the most common cause of diarrhea in the United States. Escherichia coli, Clostridium difficile and Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella spp. are common bacterial causes. Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp., and others cause food poisoning. Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Cyclospora spp. are parasitic or protozoal agents that cause diarrhea.

Acute watery diarrhea is most commonly seen with traveler's diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), parasite-induced diarrhea from Giardia and Cryptosporidium spp. and, in cases of food poisoning (ingestion of preformed toxins), from B. cereus and S. aureus.

Some infectious agents cause mucosal inflammation, which may be mild or severe. Bacteria such as enteroadherent or enteropathogenic E. coli and viruses such as rotavirus, Norwalk agent, and HIV can cause minimal to moderate inflammation. Bacteria that destroy enterocytes such as Shigella, enteroinvasive E. coli, the parasite Entamoeba histolytica and bacteria that penetrate the mucosa such as Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, and Yersinia enterocolitica result in moderate to severe inflammation with or without ulceration.

Ingestion of preformed toxin produced by bacteria such as B. cereus, S. aureus, and Clostridium perfringens can result in acute jejunitis. Aeromonas, Shigella, and Vibrio spp. (e.g., V. parahaemolyticus) produce enterotoxins and also invade the intestinal mucosa. Patients therefore often present with watery diarrhea, followed within hours or days by bloody diarrhea. Bacteria that produce inflammation from cytotoxins include Clostridium difficile and hemorrhagic E. coli 0157:H7.

Exudative diarrhea results from extensive injury of the small bowel or colon mucosa as a result of inflammation or ulceration, leading to a loss of mucus, serum proteins, and blood into the bowel lumen. Increased fecal water and electrolyte excretion results from impaired water and electrolyte absorption by the inflamed intestine rather than from secretion of water and electrolytes into the exudates.

Noninfectious causes of diarrhea include inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, ischemic bowel disease, partial small bowel obstruction, pelvic abscess in the rectosigmoid area, fecal impaction, and the ingestion of poorly absorbable sugars, such as lactulose and acute alcohol ingestion. Diarrhea is one of the most frequent adverse effects of prescription medications; it is important to note that drug-related diarrhea usually occurs after a new drug is initiated or the dosage increased.

Signs and symptoms

Clinical features sometimes provide a clue as to the cause. Diarrhea caused by small intestine disease is typically high volume, watery, and often associated with malabsorption. Dehydration is frequent. Diarrhea caused by colonic involvement is more often associated with frequent small-volume stools, the presence of blood, and a sensation of urgency.

Important factors in evaluating acute diarrhea include travel history, sources of water (e.g., well water), recent food intake, history of profuse diarrheal episodes, dehydration, fever, hematochezia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Important clinical features include abrupt versus gradual onset of symptoms, symptom duration, including bowel movement frequency, stool quantities, dysentery with fever, tenesmus, hematochezia or pus in the stool, signs of volume depletion, including thirst, tachycardia, orthostasis, decreased urine output, skin turgor, and lethargy or confusion, or both.

Patients ingesting toxins or those with toxigenic infection typically have nausea and vomiting as prominent symptoms, along with watery diarrhea, but rarely have a high fever. Vomiting that begins within 6 hours of ingesting a food should suggest food poisoning caused by preformed toxin from bacteria such as S. aureus or B. cereus. If diarrhea disease begins within 8 to 14 hours of food ingestion, C. perfringens should be suspected. When the incubation period is longer than 14 hours and vomiting is also a significant symptom, along with the diarrhea, viral agents should be considered. Parasites that do not invade the intestinal mucosa, such as Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium, usually cause only mild abdominal discomfort. Giardiasis may be associated with mild steatorrhea, gaseousness, and bloating.

Infection with invasive bacteria such as Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella spp., and organisms that produce cytotoxins, such as C. difficile and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (serotype O157:H7), frequently result in abdominal pain, and low-grade fever; occasionally, peritoneal signs may suggest a surgical abdomen. Yersinia organisms often infect the terminal ileum and cecum and manifest with right lower quadrant pain and tenderness, suggestive of acute appendicitis.

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura can occur in infections with enterohemorrhagic E. coli and Shigella organisms, particularly in young children and older adults. Yersinia infection and other enteric bacterial infections may be accompanied by Reiter's syndrome (arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis), thyroiditis, pericarditis, or glomerulonephritis. Enteric fever, caused by Salmonella typhi or paratyphi, is a severe systemic illness manifested initially by prolonged high fevers, prostration, confusion, and respiratory symptoms, followed by abdominal tenderness, diarrhea, and rash.

Epidemiologic risk factors should be investigated for certain diarrheal diseases and their spread. They include recent travel to an underdeveloped area, daycare center exposure, consumption of raw meat, eggs, shellfish, and unpasteurized milk products, contact with reptiles or pets with diarrhea, a history of other ill people in a shared dormitory facility, recent antibiotic use, and a history of HIV or medically induced immunosuppression. In cases of homosexual males, in addition to immunosuppression, there are two other disease transmission routes that lead to an increased susceptibility to infectious agents that cause diarrhea. These include an increased rate of fecal-oral transmission of all infectious agents spread by this route, including Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and intestinal protozoa and anal intercourse. Anal intercourse may lead to a direct rectal inoculation, resulting in proctitis associated with rectal pain, tenesmus, and passage of small-volume, bloody, mucous stools.

Diagnosis

Conducting a careful interview can provide valuable clues that will aid in diagnosing and choosing the most appropriate and cost-effective investigation. Acute diarrheas are usually infectious in origin and, for the most part, resolve with or without intervention before a diagnosis is made.

The presence of blood is a useful clue, suggesting infection by invasive organisms, inflammation, ischemia, or neoplasm. Large-volume diarrhea suggests small bowel or proximal colonic disease, whereas small frequent stools associated with urgency suggest left colon or rectal disease. All current and recent medications should be reviewed, specifically new medications, antibiotics, antacids, and alcohol abuse. Nutritional supplements should also be reviewed, including the intake of “sugar-free” foods (containing nonabsorbable carbohydrates), fat substitutes, milk products, and shellfish, and heavy intake of fruits, fruit juices, or caffeine. Food- or waterborne outbreaks of diarrhea are becoming more common. The history should include place of residence, drinking water (treated city water or well water), rural conditions, with consumption of raw milk, consumption of raw meat or fish, and exposure to farm animals that may spread Salmonella or Brucella organisms. Sexual history is important, because specific organisms can cause diarrhea in homosexual men and HIV-infected patients.

A medical evaluation of acute diarrhea is not warranted in the previously healthy individual if symptoms are mild, moderate, spontaneously improve within 48 hours, and are not accompanied by fever, chills, severe abdominal pain, or blood in the stool. On the other hand, evaluation is indicated if symptoms are severe or prolonged, the patient appears “toxic,” there is evidence of colitis (occult or gross blood in the stools, severe abdominal pain or tenderness, and fever), or empirical therapy has failed. Passage of many small-volume stools containing blood and mucus, temperature higher than 38.5° C (101.3° F), passage of more than six unformed stools in 24 hours, or a duration of illness longer than 48 hours, diarrhea with severe abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 years, diarrhea in older adults (older than 70 years) or in the immunocompromised patient (e.g., those with AIDS, after transplantation, or undergoing cancer chemotherapy) are all indications for a thorough medical and bacteriologic evaluation.

The physical examination in acute diarrhea is helpful in determining the severity of disease and hydration status. A directed physical examination may lead to a more focused evaluation. Vital signs (including temperature and orthostatic evaluation of pulse and blood pressure) and signs of volume depletion (including dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, and confusion) should be carefully evaluated. A careful abdominal examination to evaluate for tenderness and distention and a stool examination to evaluate for grossly bloody stools are warranted. Nonbloody stools should be evaluated for heme positivity.

The history and physical examination can help lead to a diagnosis but, for treatment of some organisms, a specific diagnosis is required, which will lead to more specific therapy and prevention of unneeded interventions. Fecal testing should be performed in patients with a history of diarrhea longer than 1 day who have the following symptoms: fever, bloody stools, systemic illness, recent or remote antibiotic treatment, hospital admission, or signs of dehydration, as described earlier.

Studies in Select Patients with Acute Diarrhea

The following studies should be carried out:

1. Fecal leukocyte determination

2. Stool culture for enteric pathogens

3. Stool examination for ova and parasites

4. Flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy

Stool evaluation for fecal leukocytes (or lactoferrin, a by-product of white blood cells) is a useful initial test, because it may support a diagnosis of inflammatory diarrhea. If the test is negative, stool culture may not be necessary, but culture is indicated if the test is positive. However, clinicians should remember that inflammatory diarrhea with a noninfectious cause, such as inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic or radiation-induced colitis, and diverticulitis, can be positive for stool leukocytes.

Indications for stool culture are bloody diarrhea, a toxic-appearing patient (fever, severe abdominal pain), possible epidemic, history of traveler's diarrhea, immunosuppression, or persistent diarrhea. A positive stool culture can be considered to be a true positive. Multiple stool cultures are usually not necessary because bacteria usually shed continuously. The culture medium routinely used can identify Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, and Aeromonas organisms. Stool cultures are of little value if first performed more than 72 hours after admission. In outbreaks of diarrhea secondary to Salmonella and E. coli, performance of routine culture is critical for antibiotic resistance testing and serotype subtyping. In patients with bloody diarrhea or hemolytic-uremic syndrome, the stool should be evaluated for E. coli 0157 by the presence or absence of Shiga's toxin. Stool culture for Vibrio spp. should be performed for those with diarrhea who have a previous history of shellfish ingestion within three days of onset of the illness. Cultures for Yersinia enterocolitica should be performed for at-risk populations (Asian Americans in California and African American infants) who develop diarrhea in the fall or winter. The rapid enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for C. difficile toxins A and B is most often used for high-risk patients who have taken antibiotics or have hospital-acquired diarrhea that develops three or more days after admission. The evaluation and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including C. difficile, are considered elsewhere in this section (“Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea”).

A negative stool culture in a patient with acute diarrhea with fecal leukocytes is helpful for suggesting the acute onset of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., Crohn's disease, mucosal ulcerative colitis). A flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy may provide additional support.

Stool testing for ova and parasites should be done if the patient is at risk for parasitic infection. Multiple stool collections should be collected at different times because shedding of parasites may be intermittent.

When organisms are not identified on stool cultures for ova and parasites, a sigmoidoscopy should be performed and biopsies obtained. Mucosal biopsy is helpful in differentiating infectious colitis from inflammatory bowel disease. Further investigations will depend on the results of sigmoidoscopy, severity of diarrhea, immune status of the host, and presence of systemic toxicity. A general algorithm for the evaluation and management of acute diarrhea is shown in Figure 1.

Algorithm for the evaluation of a patient with acute diarrhea.

Treatment

The principal components of the treatment of acute diarrhea are fluid and electrolyte replacement, dietary modifications, and drug therapy. All recommendations agree with the guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea in adults published by the American College of Gastroenterology.

Rehydration

In most cases of acute diarrhea, fluid and electrolyte replacement are the most important forms of therapy. If patients are otherwise healthy and are not dehydrated, adequate oral intake can be achieved with soft drinks, fruit juice, broth, soup, and salted crackers. In those with excessive fluid losses and dehydration, more aggressive measures such as IV fluids or oral rehydration therapy with isotonic electrolyte solutions containing glucose or starch should be instituted. Oral rehydration therapy is less expensive, often just as effective, and more practical than intravenous fluids. A number of oral rehydration solutions are available, including Pedialyte, Rehydralyte, Ricelyte (Infalyte), Resol, the World Health Organization formula, and the newer reduced osmolarity formula for children. An equally effective homemade mixture is ½ tsp salt (3.5 g), 1 tsp baking soda (2.5 g NaHCO3), 8 tsp sugar (40 g), and 8 oz orange juice (1.5 g KCl), diluted to 1 L with water. Fluids should be given at rates of 50 to 200 mL/kg/24 hr, depending on the patient's hydration status. IV fluids (e.g., lactated Ringer's solution) are preferred acutely for patients with severe dehydration and for those who cannot tolerate oral fluids.

Diet

Total food abstinence is unnecessary and not recommended. Foods providing calories are necessary to facilitate renewal of enterocytes. Patients should be encouraged to take frequent feedings of fruit drinks, tea, “flat” carbonated beverages, and soft, easily digested foods such as bananas, applesauce, rice, potatoes, noodles, crackers, toast, and soups. Dairy products should be avoided, because transient lactase deficiency can be caused by enteric, viral, and bacterial infections. Caffeinated beverages and alcohol, which can enhance intestinal motility and secretions, should be avoided.

Pharmacologic Measures

Antidiarrheal Agents

These can be useful for the amelioration of symptoms. The most effective agents are the opioid derivatives—loperamide, diphenoxylate—atropine, and tincture of opium. These agents inhibit intestinal peristalsis, facilitating intestinal absorption, and have antisecretory properties. Loperamide may reduce the duration of diarrhea in those with traveler's diarrhea and bacillary dysentery. These agents should be avoided in patients with fever, bloody diarrhea, and possible inflammatory diarrhea because they may be associated with prolonged fever in patients with shigellosis, toxic megacolon in patients with C. difficile infection, and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome in children with Shiga toxin–producing E. coli.

Bismuth subsalicylate, somewhat less effective than loperamide, is effective in relieving symptoms of diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain in patients with traveler's diarrhea. Bismuth subsalicylate is contraindicated in HIV-infected patients because it may cause bismuth encephalopathy.

Antimicrobial Treatment

Because most patients have mild, self-limited disease caused by viruses or noninvasive bacteria, routine empirical treatment is not warranted. Empirical treatment is indicated for those patients with suspected invasive bacterial infection, traveler's diarrhea, or immunosuppression. Empirical antibiotic treatment is also appropriate specifically for early Campylobacter infections and C. difficile–associated diarrhea as well as for the febrile patient with fecal leukocytes and hemoccult-positive stools. Empirical treatment for Giardia can be prescribed for those with a 2-week or longer history of diarrhea.

Stroke

Essential of Diagnosis

- Sudden onset characteristic neurologic deficit

- Patient often has history of hypertention, diabetes mellitus, valvular heart disease, or atherosclerosis

- Distinctive neurologic signs reflect the region of the brain involved

General Consideration

In the USA, stroke remains the third leading cause of death, despite a general in the incidence of stroke in the last 30 years. the precise reasons for this decline are uncertain, but increased awareness of risk factors and improved prophylactic measures and surveillance of those at increased risk have been contributory. elevarion of the blood homocysteine level is also risk factor of stroke, but it is unclear whether this risk is reduced by treatment to lower level. a previous stroke makes individual patients more susceptible to further strokes.

Definition

A stroke is defined as a sudden loss of brain function caused by a blockage or rupture of a blood vessel to the brain. Stroke can be subdivided into two types: ischemic and hemorrhagic. Ischemic stroke accounts for 85% of all cases. Hemorrhagic stroke can be further subclassified as intracerebral and subarachnoid. This chapter provides an overview of the broad field of stroke, with particular emphasis on ischemic stroke.

Pathophysiology

Ischemic Stroke

In ischemic stroke, interruption of the blood supply to the brain results in tissue hypoperfusion, hypoxia, and eventual cell death secondary to a failure of energy production.

Three main mechanisms are involved in the development of ischemic stroke, and they are associated with atherothrombotic, embolic, and small-vessel diseases. Less common causes include coagulopathies, vasculitis, dissection, and venous thrombosis.

Atherothrombotic Disease

In atherothrombotic disease, lipid deposition leads to the formation of plaque, which narrows the vessel lumen and results in turbulent blood flow through the area of stenosis. The turbulence of the flow and the resultant alterations in flow velocities lead to intimal disruption or plaque rupture, both of which activate the clotting cascade. This causes platelets to become activated and adhere to the plaque surface, where they eventually form a fibrin clot. As the lumen of the vessel becomes more occluded, ischemia develops distal to the obstruction and can eventually lead to an infarction of the tissue that is dependent on the parent vessel for oxygen delivery.

Embolic Disease

Embolic stroke occurs when dislodged thrombi travel distally and occlude vessels downstream. One-half of all embolic strokes are caused by atrial fibrillation; the rest are attributable to a variety of causes, including (1) left ventricular dysfunction secondary to acute myocardial infarction or severe congestive heart failure, (2) paradoxical emboli secondary to a patent foramen ovale, and (3) atheroemboli. These latter vessel-to-vessel emboli often arise from atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic arch, carotid arteries, and vertebral arteries.

Small-Vessel Disease

Small-vessel ischemia can occur when microatheromata occlude the orifice of penetrating arteries Another mechanism is associated with lipohyalinosis, in which pathologic changes in the tunica media and the adventitia of penetrating arteries occur in the presence of chronic hypertension. Elevated blood pressure causes endothelial injury that disrupts the blood-brain barrier. This in turn leads to a deposition of plasma proteins and eventually degeneration of the tunica media smooth muscle. The smooth muscle is replaced with collagenous fibers, which inhibit the elasticity of the blood vessel. This causes the vessel lumen to narrow and eventually activates the clotting cascade, leading to thrombosis. Small-vessel ischemic disease typically results in lacunar infarcts, which were named for the small "lakes" (lacunae) that are found at autopsy in affected patients.

Hypoperfusion can occur as a result of (1) atherosclerotic disease that limits distal flow or (2) systemic hypotension, such as seen in patients who experience acute cardiacarrhythmia or cardiac arrest. A reduction in cerebral perfusion pressure activates the autoregulatory system. As the small arterioles constrict in an attempt to maintain pressure, ischemia can develop in the distal branches of the vascular tree. Areas of the brain that lies between two major vascular supplies (eg, the middle and anterior cerebral arteries) is known as a watershed area. These areas are especially prone to ischemia during episodes of systemic hypotension.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Intracerebral hemorrhage is the result of the rupture of a vessel within the brain parenchyma. As with ischemic stroke, the location of an intracerebral hemorrhage determines the type of symptoms and the patient's overall outcome. For example, a small lobar hemorrhage might cause only a mild headache and subtle motor deficits, while a hemorrhage of the same size in the pons might result in a coma. Outcomes are also correlated with the volume of blood; hemorrhages greater than 60 ml are almost always fatal, regardless of their location

Hypertension is a major cause of hemorrhages of the basal ganglia and brainstem. Chronic hypertension can lead to the formation of Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms in lipohyalinotic vessels, which can rupture. Common locations of hypertensive hemorrhages include the putamen, caudate, thalamus, pons, and cerebellum.

Amyloid angiopathy is a common cause of lobar hemorrhage. This disease process occurs in the elderly and is caused by a deposition of beta amyloid sheets in the tunica media of the vessel wall. The deposition of amyloid protein causes the vessels to become more rigid, fragile, and prone to rupture. Evidence of hemosiderin deposition in other areas of the brain on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might also be seen. This deposition indicates that the patient has experienced previous hemorrhage and provides indirect support for the presence of amyloid angiopathy; however, pathologic examination is necessary before a definitive diagnosis can be made.

Signs and symptoms

There is tremendous variability in the signs and symptoms of stroke, but they have all been well documented. Depending on the severity of the stroke, patients can experience a loss of consciousness, cognitive deficits, speech dysfunction, limb weakness, hemiplegia, vertigo, diplopia, lower cranial nerve dysfunction, gaze deviation, ataxia, hemianopia, and aphasia, among others.

Diagnosis