Definition and causes

Eating disorders are syndromes characterized by severe disturbances in eating behavior and by distress or excessive concern about body shape or weight. Presentation varies, but eating disorders often occur with severe medical or psychiatric comorbidity. Denial of symptoms and reluctance to seek treatment make treatment especially challenging.

Classification

Major eating disorders can be classified as anorexia nervosa , bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified. Although criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM IV-TR1), allow diagnosis of a specific eating disorder, many patients demonstrate a mixture of both anorexia and bulimia. Up to 50% of patients with anorexia nervosa develop bulimic symptoms, and a smaller percentage of patients who are initially bulimic develop anorexic symptoms.

| Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa |

|---|

|

| Type |

|

| Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa |

|---|

|

| Type |

|

| Criteria for Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified |

|---|

Eating disorder not otherwise specified includes disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for any specific eating disorder.

|

| Binge-eating disorder is recurrent episodes of binge eating in the absence if regular inappropriate compensatory behavior characteristic of bulimia nervosa. |

Listed in the DSM IV-TR appendix, binge eating disorder is defined as uncontrolled binge eating without emesis or laxative abuse. It is often, but not always, associated with obesity symptoms. Night eating syndrome includes morning anorexia, increased appetite in the evening, and insomnia. Often obese, these patients can have complete or partial amnesia for eating during the night.

Eating disorders before puberty include food avoidance emotional disorder, which is similar to anorexia; selective eating of only a few foods; pervasive refusal syndrome, with reduced intake and added behavioral problems; and functional dysphagia with no organic etiology. Unpleasant mealtimes and conflicts over eating can precede these conditions of childhood. Pica and rumination are not considered eating disorders, but rather are feeding disorders of infancy and childhood.

Gender Prevalence

Both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are more commonly seen in girls and women. Estimates of female-to-male ratio range from 6 : 1 to 10 : 1.

Lifetime Prevalence

The reported lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa among women has ranged from 0.5% when narrowly defined to 3.7% for more broadly defined anorexia nervosa. With regard to bulimia nervosa, estimates of lifetime prevalence among women range from 1.1% to 4.2%. Prevalence of eating disorders in young children is unknown. However, children as young as 5 years have reported awareness of dieting and know that inducing vomiting can produce weight loss. Eating disorder not otherwise specified is the most prevalent eating disorder.

Cultural Considerations

Eating disorders are more common in industrialized societies where there is an abundance of food and being thin, especially for women, is considered attractive. Eating disorders are most common in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. However, rates are increasing in Asia, especially in Japan and China, where women are exposed to cultural change and modernization. In the United States, eating disorders are common in young Latin American, Native American, and African American women, but the rates are still lower than in white women. African American women are more likely to develop bulimia and more likely to purge. Female athletes involved in running, gymnastics, or ballet and male body builders or wrestlers are at increased risk.

Pathophysiology and natural history

Biologic and psychosocial factors are implicated in the pathophysiology, but the causes and mechanisms underlying eating disorders remain uncertain.

Biologic Factors

First-degree female relatives and monozygotic twin offspring of patients with anorexia nervosa have higher rates of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Children of patients with anorexia nervosa have a lifetime risk for anorexia nervosa that is tenfold that of the general population (5%). Families of patients with bulimia nervosa have higher rates of substance abuse, particularly alcoholism, affective disorders, and obesity.

Endogenous opioids might contribute to denial of hunger in patients with anorexia nervosa. Some hypothesize that dieting can increase the risk for developing an eating disorder. Increased endorphin levels have been described in patients with bulimia nervosa after purging and may be likely to induce feelings of well being. Diminished norepinephrine turnover and activity are suggested by reduced levels of 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol in the urine and cerebrospinal fluid of some patients with anorexia nervosa. Antidepressants often benefit patients with bulimia nervosa and support a pathophysiologic role for serotonin and norepinephrine.

Starvation results in many biochemical changes such as hypercortisolemia, nonsuppression of dexamethasone, suppression of thyroid function, and amenorrhea. Several computed tomography (CT) studies of the brain have revealed enlarged sulci and ventricles, a finding that is reversed with weight gain. In one study using positron emission tomography (PET), metabolism was higher in the caudate nucleus during the anorectic state than after hyperalimentation.

Anorexia risk may increase with a polymorphism of the promoter region of serotonin 2a receptor. The melanocortin 4 receptor gene is hypothesized to regulate weight and appetite. Polymorphism in the gene for agouti-related peptide might also play a role at the melancortin receptor. In bulimia nervosa there is excessive secretion of ghrelin. Ghrelin receptor gene polymorphism is associated with both hyperphagia of bulimia and Prader-Willi syndrome.

Perhaps some of the most fascinating new research addresses the overlap between uncontrolled compulsive eating and compulsive drug seeking in drug addiction. Reduction in ventral striatal dopamine is found in both of these groups. The lower the frequency of dopamine D2 receptors, the higher the body mass index. Obese persons might eat to temporarily increase activity in these reward circuits. Frequent visual food stimuli paired with increased sensitivity of right orbitofrontal brain activity is likely to initiate eating behavior. Marijuana's well-known appetite stimulant effect is likely due to its agonist activity at cannabinoid receptors, and cannabinoid receptor antagonism has been associated with reduced binge eating.

Psychosocial Factors

High levels of hostility, chaos, and isolation and low levels of nurturance and empathy are reported in families of children presenting with eating disorders. Anorexia has been postulated as a reaction to demands on adolescents to behave more independently or to respond to societal pressures to be slender. Anorexia nervosa patients are usually high achievers, and two thirds live at home with parents. Many consider their bodies to be under the control of their parents. Family dynamics alone, however, do not cause anorexia nervosa. Self tarvation may be an effort to gain validation as a unique person. Patients with bulimia nervosa have been described as having difficulties with impulse regulation.

Course and Prognosis

As a general guideline, it appears that one third of patients fully recover, one third retain subthreshold symptoms, and one third maintain a chronic eating disorder.

Anorexia Nervosa

Long-term follow-up shows recovery rates ranging from 44% to 76%, with prolonged recovery time (57 to 59 months). Mortality (up to 20%) is primarily from cardiac arrest or suicide. Good prognostic factors are admission of hunger, lessening of denial, and improved self esteem. Poorer prognostic factors are initial lower minimum weight, presence of vomiting or laxative abuse, failure to respond to previous treatment, disturbed family relationships, and conflicts with parents.

Bulimia Nervosa

Little long-term follow-up data exist. Short-term success is 50% to 70%, with relapse rates between 30% and 50% after 6 months. These patients have an overall better prognosis as compared with anorexia nervosa patients. Poor prognostic factors are hospitalization, higher frequency of vomiting, poor social and occupational functioning, poor motivation for recovery, severity of purging, presence of medical complications, high levels of impulsivity, longer duration of illness, delayed treatment, and premorbid history of obesity and substance abuse.

Signs and symptoms

Anorexia Nervosa

The essential features of anorexia nervosa are refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight, intense fear of gaining weight, and significant disturbance in the perception of the shape or size of one's body. Patients commonly lack insight into the problem and are brought to professional attention by a family member. DSM IV-TR identifies two subtypes of anorexia nervosa: restricting type and binge eating–purging type. Comorbid psychiatric symptoms include depressive symptoms such as depressed mood, social withdrawal, irritability, insomnia, and decreased sexual interest. Many depressive features may be secondary to the physiologic sequelae of semistarvation. Symptoms of mood disturbances need to be reassessed after partial or complete weight restoration. Obsessive-compulsive features—thoughts of food, hoarding food, picking or pulling apart small portions of food, or collecting recipes—are common. Anxiety symptoms and concerns of eating in public are also common.

Bulimia Nervosa

The essential features are binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behavior such as fasting, vomiting, using laxatives, or exercising to prevent weight gain. Binge eating is typically triggered by dysphoric mood states, interpersonal stressors, intense hunger following dietary restraints, or negative feelings related to body weight, shape, and food. Patients are typically ashamed of their eating problems, and binge eating usually occurs in secrecy. Unlike anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa patients are typically within normal weight range and restrict their total caloric consumption between binges.

Diagnosis

Rating Instruments

In addition to the clinical interview, the Eating Attitudes Test, Eating Disorders Inventory, Body Shape Questionnaire, and others can be used to assess eating disorders.

Comorbidity of Eating Disorders

Psychiatric

Common comorbid conditions include major depressive disorder or dysthymia (50% to 75%), sexual abuse (20% to 50%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (25% with anorexia nervosa), substance abuse (12% to 18% with anorexia nervosa, especially the binge–purge subtype, and 30% to 37% with bulimia nervosa), and bipolar disorder (4% to 13%).

Medical

There are many complications related to weight loss, purging and vomiting, and laxative abuse. When obesity is associated with the eating disorder, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, joint injury, hypertension, and cardiac and respiratory disorders can result.

| Medical Complications of Eating Disorders |

|---|

| Weight Loss |

|

| Appetite Suppressant Abuse |

|

| Purging (Abuse of Laxatives, Ipecac, or Diuretics) |

|

Differential diagnosis

Anorexia Nervosa

Medical illnesses include brain tumors and other malignancies, gastrointestinal disease, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Other psychiatric disorders with disturbed appetite or food intake include depression, somatization disorder, and schizophrenia. Patients with depressive disorder generally do not have an intense fear of obesity or body image disturbance. Depressed patients usually have a decreased appetite, whereas anorexia nervosa patients claim to have a normal appetite and to feel hungry. Patients with somatization disorder do not generally express a morbid fear of obesity. Severe weight loss and amenorrhea of more than 3 months are unusual in somatization disorder. Schizophrenic patients might have delusions about food being poisoned but rarely are they concerned with caloric content. They also do not express a fear of gaining weight.

Bulimia nervosa patients usually maintain their weight within a normal range.

Bulimia Nervosa

General medical conditions of central nervous system pathology, such as brain tumors, can simulate bulimia nervosa. Kluver-Bucy syndrome is a rare condition characterized by hyperphagia, hypersexuality, and compulsive licking and biting. Klein-Levin syndrome, also rare, is more common in men and consists of hyperphagia and periodic hypersomnia.

Patients with the binge–purge subtype of anorexia nervosa fail to maintain their weight within a normal range. Patients with borderline personality disorder sometimes binge eat but do not have other criteria for bulimia nervosa.

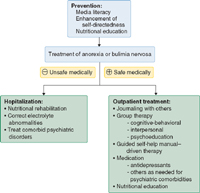

Treatment

A comprehensive treatment plan including a combination of nutritional rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and medication is recommended. The patient's weight and cardiac and metabolic status determines the acuteness of the illness and the need for hospitalization. Treatment guidelines are well documented by the American Psychiatric Association in its practice guideline for treating eating disorders.

| Indications for Hospitalization |

|---|

| Weight <75% of individually estimated healthy weight |

| Rapid, persistent decline in oral intake or weight despite maximally intensive outpatient interventions |

| Prior knowledge of weight at which physical instability is likely to occur in the particular patient |

Serious physical abnormalities

|

| Comorbid psychiatric illness (suicidal, depressed, unable to care for self, etc.) |

Aims of treatment are to restore the patient's nutritional status and establish healthy eating patterns, treat medical complications, correct core dysfunctional thoughts related to the eating disorder, enlist family support, and provide family counseling.

Nutritional Rehabilitation

Expected rates of controlled weight gain should be 2 to 3 pounds per week for inpatients and 0.5 to 1 pound per week for outpatients. Intake levels should start at 30 to 40 kcal/kg per day (1000-1600 kcal/day) in divided meals. If oral feeding is not possible, progressive nocturnal nasogastric feeding can lessen distress (physical and psychological) during early weight gain.

Daily morning weights, vital signs, fluid intake, and urine output should be measured. Frequent physical examinations should be performed to detect circulatory overload, refeeding edema, and bloating. Monitor serum electrolyte levels (low potassium or phosphorus), and get an electrocardiogram if needed.

Stool softeners, not laxatives, should be used to treat constipation. The diet should be supplemented with vitamins and minerals.

Patients should be given positive reinforcement (praise) and negative reinforcement (restrictions of exercise and purging). They should be closely supervised, and access to bathrooms should be restricted for at least 2 hours after meals. After weight restoration has progressed, stretching can begin, followed by gradual re-introduction of aerobic exercise.

Psychosocial Treatment

Psychosocial treatments are required during hospitalization as well as after discharge. Commonly used models include dynamic expressive-supportive therapy and cognitive-behavioral techniques (planned meals and self-monitoring, exposure, and response prevention). Research data more strongly support the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapies. Although cognitive-behavioral therapy is important, its benefits increase with the addition of a nutritional component.

Group therapy, support groups, and 12-step programs like Overeaters Anonymous may be useful as adjunctive treatment and for relapse prevention. Family therapy and marital therapy are helpful in cases of dysfunctional family patterns and interpersonal distress.

Guided self-help manuals can reduce the number of binge–purge episodes in at least some patients with bulimia nervosa. In fact, a manual-driven self-help approach incorporating cognitive-behavioral principles combined with keeping contact with a general practice physician in one study did as well as specialist-based treatment in reducing bulimic episodes. Computer-based health education can improve knowledge and attitudes as a patient-friendly adjunct to therapy.

One unique approach is a behavioral family-based therapy for elementary school–age children with behavioral problems, disordered eating, and obesity. Children and parents were examined and tested before and after the intervention and all lost weight. Although eating disorders did not resolve, other behavioral problems did. There was less parental dissatisfaction as children developed better awareness and behavior patterns.

Higher self-directedness at baseline is a good predictor of improvement at the end of a variety of interventions, as well as follow-up 6 to 12 months later. This might help explain why manual-driven self-help and psychoeducational programs that emphasize improvement of self-esteem and reassessment of body image have achieved some success.

Medication

Anorexia Nervosa

The evidence for significant efficacy is lacking, with very few methodologically sound studies. Although medication is less successful in anorexia nervosa than in bulimia nervosa, it is most often used in anorexia nervosa after weight has been restored but may begin earlier when indicated. Medication helps maintain weight and normal eating behavior and can treat associated psychiatric symptoms.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., fluoxetine) are commonly considered for patients with anorexia nervosa who have depressive, obsessive, or compulsive symptoms that persist in spite of or in the absence of weight gain. Tricyclic antidepressants are also effective in treating eating disorders. However, they should be used with caution, because they have greater risks of cardiac complications, including arrhythmias and hypotension.

Low doses of antipsychotics may be used for marked agitation and psychotic thinking, but they can frighten patients by increasing appetite dramatically, particularly if the patient is not psychotic. Antianxiety medications, such as benzodiazepines, may be used for extreme anticipatory anxiety concerning eating.

Estrogen replacement alone does not generally appear to reverse osteoporosis or osteopenia, and unless there is weight gain, it does not prevent further bone loss. There is very limited evidence of bisphosphonate's efficacy in treating associated osteoporosis.

Promotility agents such as metoclopramide are commonly used for bloating and abdominal pains due to gastroparesis and premature satiety, but they require monitoring for drug-related extrapyramidal side effects.

Recombinant human growth hormone has helped stabilize patients medically in shorter hospital stays.

Bulimia Nervosa

Antidepressants are used primarily to reduce the frequency of disturbed eating and treat comorbid depression, anxiety, obsessions, and certain impulse-disorder symptoms. Medication can reduce binge episodes, but is not sufficient to be the sole treatment. The only medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for bulimia nervosa is the SSRI fluoxetine (Prozac). Several studies have demonstrated efficacy of other SSRIs including sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), and citalopram (Celexa); tricyclic antidepressants including imipramine (Tofranil), nortryptyline (Pamelor), and desipramine (Norpramin); and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) including tranylcypromine (Parnate). Doses of tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs parallel those used to treat depression, but higher doses of fluoxetine (up to 80 mg/day) may be needed to treat bulimia nervosa. Bupropion (Wellbutrin) has been associated with seizures in purging bulimic patients and its use is not recommended.

Other psychotropic drugs are sometimes used. Lithium continues to be used occasionally as an adjunct for comorbid disorders. Various anticonvulsants have successfully reduced binge eating for some patients, but they can also increase appetite. Topiramate lowers appetite but has been associated with cognitive side effects. Sibutramine has also been used to reduce appetite in bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.

Screening and prevention

Prevention programs presented in schools to both genders or through organizations like the Girl Scouts have been successful in reducing risk factors for eating disorders. Often focusing on media literacy and interactive discussion, there are increasing reports of short-term and longer-term benefits in body satisfaction and acceptance of normal growth.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar